Drafting a Shareholder Agreement that Fits Your Family’s Needs

This post is based on the article “Addressing the theory-practice divide in family business research: The case of shareholder agreements”, published in the Journal of Family Business Strategy in 2021.

Shareholder agreements are among the most consequential governance tools in a family enterprise. They determine who can own shares, under what circumstances shares may be sold, whether ownership can move outside the family, and what expectations are attached to being an owner.

Yet in many cases, these agreements are drafted at moments of urgency – during succession, after a conflict, or when ownership becomes dispersed across siblings or cousins. And as we well know, urgency is rarely a good advisor. When speed becomes the priority, families often bypass the thoughtful, inclusive process required to design something durable.

What is more, shareholder agreements are frequently based on templates or so-called “best practices.” Instead of reflecting a family’s idiosyncratic values and goals, they are adapted from what worked elsewhere, often without sufficient consideration of the distinct needs, dynamics, and constraints of the family at hand. As a consequence, few families have a shareholder agreement that truly supports them in becoming the ownership group they aspire to be.

Moving Beyond Templates

In academic research, we know surprisingly little about how shareholder agreements function in family firms. In practice, however, they are treated as essential instruments for preserving control, maintaining unity, and protecting long-term continuity. Legal and financial discussions typically focus on technical mechanisms – buy-sell clauses, voting arrangements, redemption formulas – but they rarely account for what makes family enterprises fundamentally different: the coexistence of financial and non-financial objectives, and the emotional, relational, and value-based dynamics of the owning family.

When poorly aligned with the family’s underlying characteristics, shareholder agreements can unintentionally intensify conflict, entrench divisions, or introduce rigidity that undermines trust and business agility. When thoughtfully designed, they can clarify expectations, reinforce shared values, and support continuity across generations.

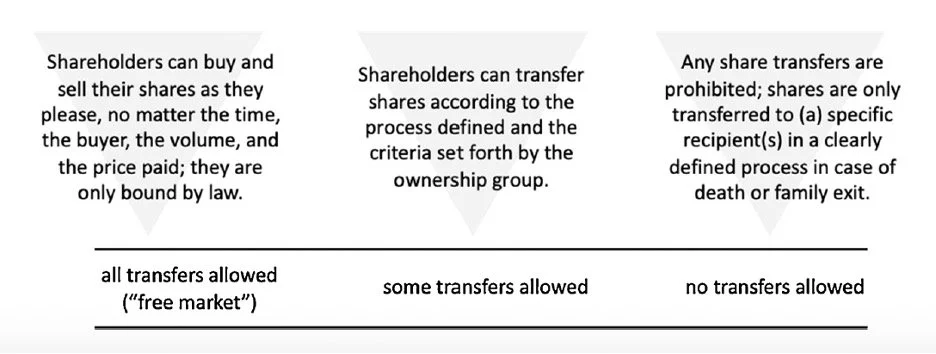

Practically speaking, shareholder agreements vary along four key dimensions: liquidity, openness, development, and flexibility. Liquidity concerns the ease with which shares can be sold or redeemed. Openness addresses whether ownership may move outside the family or include in-laws and other related parties. Development refers to whether ownership is conditional upon certain qualifications, such as education, experience, or active involvement. Flexibility captures the extent to which rules can adapt to changing circumstances.

There is no inherently “correct” configuration along these dimensions. The critical question is whether the chosen configuration aligns with the family’s values, and with its capacity to manage the consequences of those choices.

As the figure below illustrates, shareholder agreements exist on a continuum ranging from highly liberal to highly restrictive. One family may be entirely comfortable with a free-market logic in which shares are traded across branches and generations. For another family — particularly one marked by entrenched branch logics and fragile communication — such openness could quickly destabilize relationships.

Fig. 1: Family shareholder agreement continuum

A lasting and effective shareholder agreement reflects three realities: what the family values, what goals it pursues, and what capacity it has to communicate, resolve conflict, and engage future generations of owners and stewards.

The conclusion is straightforward: there is no universally good shareholder agreement. There is only one that fits (or does not fit) your family.

The Importance of Fit

Drawing on theories of strategic fit, our research suggests that governance practices are most effective when they align with the characteristics of the system in which they operate. Families differ enormously in what they prioritize. Some emphasize stewardship, community responsibility, and long-term employment stability. Others prioritize liquidity, individual autonomy, or financial return. Still others stress meritocracy and professionalization, believing ownership should be tied to demonstrated competence or contribution.

A highly restrictive agreement that limits share transfers may express a strong desire to preserve control and prevent fragmentation. An agreement that allows greater liquidity and flexibility may signal a commitment to fairness and individual freedom. Conditioning ownership on education or experience may reflect a belief in earned responsibility.

Tensions arise when the agreement sends a message inconsistent with the family’s stated values. A family that sees itself as inclusive and generous but adopts rigid exclusionary clauses may eventually confront disillusionment. Conversely, a family that values unity and stewardship may undermine those goals by allowing unrestricted external sales.

Before adopting or revising a shareholder agreement, families benefit from stepping back and asking fundamental questions:

What are our primary ownership-related goals? Are we seeking to preserve control, provide liquidity, promote meritocracy, ensure fairness, or maintain unity? Which of these goals takes precedence when trade-offs arise?

How mature are we as an ownership group? Do we possess the trust, communication skills, and competence necessary to handle dispersed ownership? Are we prepared for the conflicts that may arise under our chosen structure?

Finally, does our current or proposed agreement reinforce our stated values, or contradict them?

Designing for Longevity

For families with a multigenerational vision, shareholder agreements are foundational instruments. They shape how ownership evolves as the family grows, how capital is managed, and how commitment is sustained over time.

There is no universal template that guarantees success. What works beautifully for one family may be destabilizing for another. Rather than asking what most families do, the more important question is what fits your family’s values, goals, and level of maturity, both today and as you evolve.

Equally important is recognizing that the process of drafting a shareholder agreement may be as consequential as the document itself. If family members are excluded from meaningful participation, emotional commitment will be limited and compliance reluctant. By contrast, a thoughtful and inclusive process can clarify shared goals, surface assumptions, strengthen ownership competence, and build cohesion.

A shareholder agreement should not merely protect assets. It should support alignment, reinforce identity, and strengthen the family’s capacity to steward the enterprise across generations.